On 28th February 2014 Lila Oriard presented her Ph.D thesis in progress at DPU, Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London at SBST, CEPT.

The focus of her thesis is on the long-term social, political and economic effects of street vending analyzing the case of the City Market in Mexico City. The research uses Systems Theory approach to establish relations between apparently disconnected elements and Henri Lefebvre’s ‘Production of Space’ theory referring to space as a commodity.

The case study shows how street vending in Mexico City has changed the communities to adapt and survive with changing times and policies to evolve and finally become an integral part of the society, not without conflicts.

This work shows the potential of the streets to support a dynamic economy, offering considerable employment opportunities for many people, but at the same time it highlights the risks involved in increasing the land value of public spaces as it creates a real estate market and threatens the actual status quo of public space as ‘open to all’.

Though street vending in Mexico has been an ages old business selling local needs and cottage industry products, the modernization brought by the post half of the 19th Century led to prohibition of street vending by law in 1951, with the motive to modernize market space the Government evicted vendors from the city centre, but they continued to settle on streets which led to violent repression and formation of informal organizations amongst them. Finally the Government had to agree upon a mutually beneficial solution. This led to relocation of vendors to closed markets and modernization of Lagunilla Market by replacing wooded stalls with warehouses but most vendors were not fit for shops and returned to street vending while these closed markets became important commercial points attracting more street vendors. Political parties soon realized that permitting street vending would make vendors as well as the middle class satisfied leading to formation of political alliances at local level and hence they developed an intelligent political strategy facilitating vendors.

In the 1960’s the market was mostly in an unorganized state leading to emergence of spontaneous leaderships. This process started centralizing the informal organizations from their decentralized past nature.

These leaders not only exploited and increased the commercial potential of the market but also served as street managers collecting allowances from vendors for maintaining spaces and organizing community events.

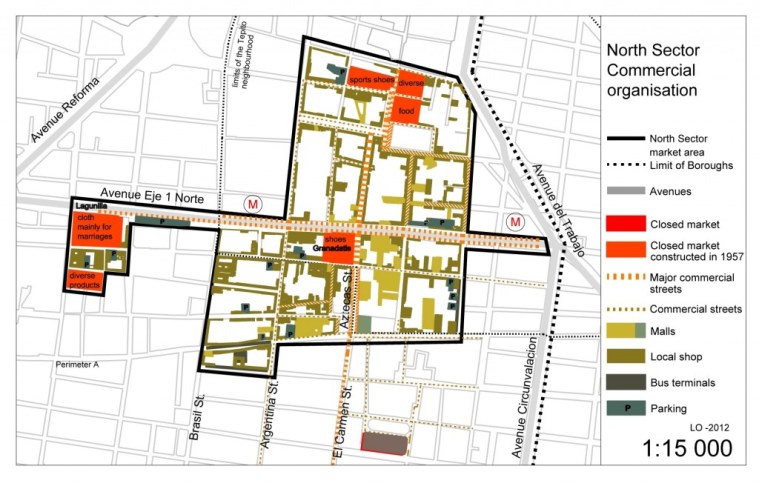

In 1980 UNESCO declared Perimeter A as monument zone and the 1985 earthquake drastically affected the city centre. During the reconstruction of city centre in 1990’s the vendors were evicted from Perimeter A and as street vending was technically illegal no formal arrangements were made to accommodate them. So during the 1980’s and early 1990’s the vendors formed confederations to sustain the eviction drive and unfolded their stalls to occupy more space needed to accommodate vendors evicted from Perimeter A, thus consolidating the city centre. In order to play fair and maintain political alliances the city government allocated plots to vendors in the unplanned northern part for construction of plazas; most plazas constructed by vendors are two storeyed spaces where the ground floor is used for retail while the first floor for storage but mostly they just complement the market activities with parking, eateries, etc.

In 1993 modifications were made in the prohibition laws that allowed street vending during festivities and this ambiguity facilitated negotiations preventing eviction of vendors, thus integrating city management and empowering the associations, especially the leaders. In 2000 the city centre was reconstructed and later in 2007 fifteen thousand vendors were evicted from the city centre and relocated in the northern Sector. Territories were renegotiated among vendors.

With time street vending has evolved to become a complex but coherent organization. The Granaditas Market selling locally manufactured shoes was constructed in 1957; in coherence to this more than half of the vendors on the nearby streets sell clothes while a tenth of them sell accessories, so basically the market as a whole serves as a fashion store. Meanwhile for manufacturing, residences with workshops are arranged around a courtyard and each family manufactures a particular part of an article which is then passed on to the neighbour thus forming an assembly line production unit; this also helps promote neighbour relations. Such arrangements in market and residential areas have led to formation of coherent spaces. Earlier street vending was restricted to local produce but after the liberalization of imports in the 1990’s one fifth of the vendors sell imports from Asia while the majority still sells local products. Consolidation and organization of space increased its value by multiple folds to as much as a 100 USD per square meter per month. Other weekly costs include a licensing fee and street rent costing a total of around 35 USD. These increasing rents have also given rise to a real estate business as today vendors running family inherited stalls or owning the space since long form only a half while the remaining one fifth are new vendors and one-third are entrepreneurs on rent. More than half of the vendors live in the city centre or nearby while the remaining ones have settled in the periphery areas. Today two hundred square meters of market space on the street creates direct employment for around two seventy, apart from the employments in manufacturing and supply chain. These local businesses have developed multi-level distribution networks for import and export. For exporting a product like a wrestling mask produced at a nearby place the cost increases by as much as 250 per cent by the time it reaches the final consumer in another part of the globe while for importing a product like leather wallet from China the cost increases by 50 per cent when finally sold on the streets of Mexico City.

With the increase in the associated value of space and subsequently the community’s pursuit to exploit and extract the most out of it, the community had to sacrifice valuable open spaces for parking or vending spots.

With increasing pressure and demand the community developed competitive relations decreasing time for convivial activities. With festivities as the best time for business vendors are barely left with any leisure time. The street took away all the attention from the house but the positive side is that those once poor have now emerged as the middle class and now there are new age entrepreneurs revolutionizing the business with imports and exports across the globe.

As for the dark side, these street markets serve as a buffer zone to the drug dealers for their illegal activities and when the powerful community leaders try to stop them, they resort to violence to terrorize the local community and maintain their right on the streets. In spite of being the users, majority of the city’s population has not yet accepted street vending as an integral part of the society, maybe because of the illegal activities in the backdrop. Nevertheless, there are still lots of improvements to be done. Street vending needs to be integrated in the city planning and management policies for ease of operation and acceptance in the society.

This article was originally published on CEPT Portfolio.

Header Image: Flickr: Shannon Michele